Bangladesh perhaps has not bid farewell to a year on a weaker note like it is going to do today in recent memory.

When it welcomed 2023, most of the economic indicators were already smarting from the woes left behind by the coronavirus pandemic and global supply chain disruptions.

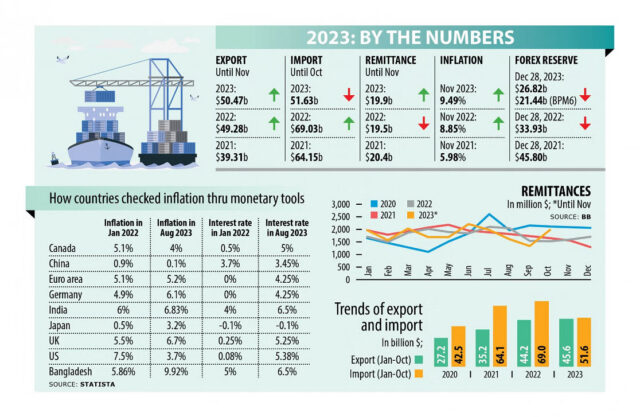

Inflation had surged to record levels, foreign currency reserves plunged, the taka dipped, exports were in the slow lane, remittance inflows did not live up to expectations, and the banking sector saw troubles – all combined together to bring about a major crisis for the economy.

The optimists might have thought that the economy had seen its worse, learnt its lesson and would make a fresh beginning in 2023. Unfortunately, that had not happened because of both external and internal factors, keeping the country on edge throughout the next 12 months.

Therefore, as 2023 comes to a close, the condition of almost all economic indicators has worsened.

Foreign currency reserves have more than halved compared to two years ago. Inflation had hovered around 9 percent. The taka has fallen further. Exports and remittance earnings have been disappointing. Imports fell but are still at a higher level. Non-performing loans at banks and irregularities remain unabated.

For the second year running, the stock market brought almost nothing for investors amid continuous fall in earnings of the listed companies owing to deepening economic and political uncertainty and the floor price.

The difficulty of making ends meet amid higher inflation and slower wage growth means low-income groups suffered a low-quality life for the second consecutive year in 2023.

But it was not all doom and gloom.

Although it unmasked the economy’s cracks, completing the loan negotiating with the IMF and the subsequent release of two installments could be seen as a major achievement of the government as it would not only help the country manage the balance of payments crisis, the conditions would force the government to put in place some reforms that were long overdue.

When it comes to infrastructure development, 2023 was perhaps the best year for the country since several major projects were completed.

The long-awaited Dhaka Elevated Expressway opened to the public in September, serving as an alternative route to and from the airport road, one of the busiest in the capital city.

The 82-kilometre rail line from Dhaka to Bhanga via the Padma Bridge has opened a new horizon for cheaper rail connectivity in the southwestern region.

The country’s first tunnel, named after Bangabandhu Sheikh Mujibur Rahman, built under the Karnaphuli river opened in October while the new terminal at the Hazrat Shahjalal International Airport and Cox’s Bazar rail station could accelerate connectivity.

But those milestones, which are expected to give a much-needed fillip to the bruised economy, were dwarfed by the widening cracks in the economy and the outlook remains deeply uncertain.

In order to restore macroeconomic stability, some policy measures were taken from the middle of the year, largely because of the International Monetary Fund’s conditions tagged with its $4.7 billion loan, although local experts and think-tanks have long called for identical moves for years.

In a major move, the central bank has withdrawn the interest rate cap on loans. However, it remains to be seen whether the new reference rate used to fix the interests of loans will live up to the expectations since the rate-setting is determined by treasury bills, meaning it might not be fully market-based.

The central bank said it has stopped printing money to keep the government operational. It has also tightened rules to limit imports and protect the reserves.

The policy rate has been increased multiple times to lift it to a record level with a view to countering the escalated inflation but the interest-rate cap made the monetary policy tool ineffective.

The adoption of a unified exchange rate has been welcomed but the IMF has stressed that a gradual transition to a more flexible regime is needed to enhance the economy’s resilience to external shocks.

Md Zaved Akhtar, chairman and managing director of Unilever Bangladesh Ltd, said businesses and policymakers had collectively missed the opportunity to put in place fundamental corrections like market-based foreign exchange rates, good governance in building strong financial institutions, and prudence in financial account management during peacetime, “making us vulnerable during the current volatile economic period.”

“As we move into 2024, we need to review our actions as businesses and policymakers. We will require a different playbook to address some of the fundamental headwinds.”

Policymakers might have hoped that the troubles at home would be resolved once the external factors responsible for the crisis in Bangladesh go away.

But Zahid Hussain, a former lead economist of the World Bank Bangladesh, says: “This assumption did not serve us well in 2023. The time is ripe to own up to the weaknesses of our unorthodox policy models and frameworks.”

He said one hopes the long overdue policy corrections will not procrastinate on the assumption that the global headwinds will fade sooner than later.

In fact, 2024 could see significant political upheaval and economic instability globally.

As countries representing 60 percent of the global GDP head to the polls, governments, businesses, and households are adopting a widespread ‘wait-and-see’ attitude that will likely delay critical economic decisions, according to the Economic Outlook 2023-25 of Allianz Research.

It warns that such uncertainty could act as a negative supply shock, potentially raising prices and curtailing output, investment and consumption.

Global growth is set to remain modest, with the impact of the necessary monetary policy tightening, weak trade and lower business and consumer confidence being increasingly felt, said the OECD’s latest Economic Outlook.

The US is on course for a ‘soft landing,’ despite facing economic headwinds. Conversely, the eurozone is grappling with near-zero growth and is forecast to dip briefly into a technical recession.

If the two regions, home to about 60 percent of Bangladesh’s total exports and 80 percent of garment shipment, face volatility, the country’s export sector would continue to be under strain.

Birupaksha Paul, a professor of economics at the State University of New York at Cortland, blamed the lack of knowledge-based leadership at financial institutions for the delayed response to the current shocks.

He said the interest-rate cap was justified by policymakers whereas other economies kept on raising policy rates to combat inflation. And they, including the neighbouring economies, were successful in reducing inflation and avoiding the dollar crisis, but Bangladesh failed in both.

Another area of policy tardiness happened in the exchange rate, which kept the dollar’s value artificially much lower than required, worsening both the current account and eventually the forex reserves, according to Prof Paul, also a former chief economist of the Bangladesh Bank.

“Further reserve depletion and moderately high inflation will keep on harming the economy if the government does not ensure knowledge-based leadership at financial institutions and make both interest and exchange rates soundly market-based.”

Rizwanul Islam, a former special adviser to the employment sector at the International Labour Office in Geneva, said the new year would provide the policymakers an opportunity to make a new beginning. But that opportunity will have to be used quickly and effectively if further deterioration of the economic condition is to be avoided.

He thinks the first task would be to fix the macroeconomic imbalances that have been acting as a brake on the economy for more than a year now.

In the outgoing year, Bangladesh could not bring down inflation whereas it has come under control in most countries. The country’s failure to discipline the vested quarters behind the commodity market volatility was visible.

To fight inflation, the economist says, action will be needed on multiple fronts.

If the interest rate is raised, its impact is likely to come with a time lag. During the interim period, supply-side interventions will be needed, especially for items that are sensitive to price fluctuations.

“Advance estimation of import requirements and better planning and implementation of imports are essential. Measures should be undertaken to protect the poor from the adverse effects of inflation,” Islam said.

Since the economy does not show any signs of an immediate return to the pre-crisis level, much of the uncertainty that haunted people and businesses over the year might not go away. So, the question arises whether people, businesses and the economy will be able to keep their head above water in 2024 if real changes take longer than they should.