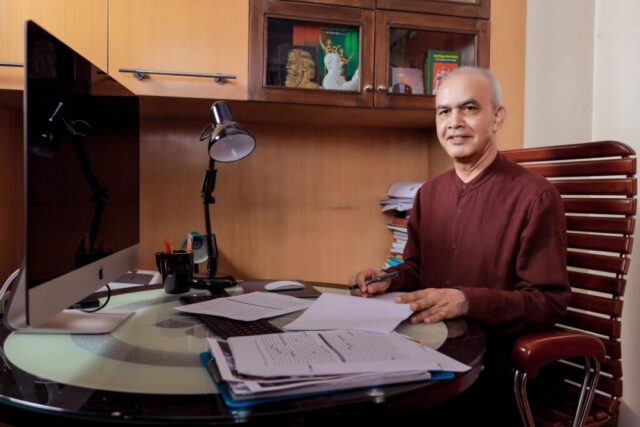

Dr. Jamaluddin Ahmed, FCA

General Secretary, Bangladesh Economic Association

Former Chairman, Janata Bank Limited

Former Member of Board of Directors, Bangladesh Bank

Former President, Institute of Chartered Accountants of Bangladesh

The words Financial Architect, fashioned into unquestionable perfection, has become ever so synonymous with the work that Dr. Jamaluddin Ahmed has accomplished. As a creative financial expert and discreet Chartered Accountant, the receiver of the exceptionally prestigious Commonwealth Scholarship from outside of academics, from his early years’ indications of his wit and talent, has now become an axiomatic phenomenon.

Just by his background, both in his education as a Ph.D. awardee on “The Adverse Effect of Devaluation on the Foreign Currency Loan User Enterprises of Bangladesh” from the Cardiff Business School, University of Wales (1996). Dr. Jamal is holder of numerous positions in various organizations, his esprit for earmarking into the insight of financial models and systems would suffice the trail that he has left behind for future economic doers.

As a former student of Dhaka University, the flagship bearer of modernizing the Bangladesh financial sector started from ground zero. Since then, we have seen an excellent steady progression in his career. Dr. Jamal has many years of experience in Bangladesh’s financial sector and has used his expertise and knowledge to carry out numerous research work and 50+ publications on Accounting, Auditing, Banking, Tax Revenue, and Corporate Governance. He was tax advisor for many local and multinational companies. Dr. Jamal was a Member of the Board of Directors of Janata Bank Limited (2008-2014) Chairman of Audit Committee (2010-2014) and served as Chairman of the Bank (2019-2020).

Dr. Jamal served Power Grid Company of Bangladesh Limited (2004-2019) as Board Member and Chairman Audit Committee and was a member of the Board and Chairman of Audit Committee of the JICA Financed Coal Power Generation Company of Bangladesh Ltd (2014-2019) the largest Project taken by Japan Government since its inception in 1961. He was also the Member of Board of Directors and Chairman of Audit Committee of Grameen Phone Limited (2010-2014). Advisor to the Board and Audit Committee of Bangladesh Bank, performed as a member of Board of Directors and Audit Committee. He was a partner at Deloitte Touche & Tohmatsu Bangladesh office. He has taken many training courses in the power and energy sector and has completed assignments at numerous banks. As the General Secretary of Bangladesh Economic Association (2015-to date) Dr. Jamal was worked as Co-Author with Professor Abul Barkat “Alternate National Budget for the country-to Develop on the Spirit of Liberation War of Bangladesh.” He participated at Harvard University Seminar on Rising Bangladesh in 2018.

The languages and even the logic would not enough what Dr. Jamaluddin Ahmed gradually did for the institutions that he worked for, the nationalistic endeavor in everything done by him makes him one of the most regarded professionals in the history of Bangladesh.

The InCAP team discussed various issues with him for a long time, which can be entitled “In Search of Designing of An Effective Financial System for Economic Growth”. So this time, we are publishing in the form of a thesis, apparently not like an interview. It’s a complete financial artwork which is written by Dr. Jamaluddin Ahmed.

In Search of Designing of an Effective Financial System for Economic Growth

A crucial aspect of the industrialization process is the development of an institutions dealing with the transfer of payments and mediating the flow of savings and investment. While all industrial societies have such a specialized financial system, cross-national comparison of these systems indicates considerable structural diversity (Zysman 1983). One key difference is the degree to which financial systems are bank-based or market-based. In bank-based systems, the bulk of financial assets and liabilities consist of bank deposits and direct loans. In market-based systems, securities that are tradeable in financial markets are the dominant form of financial asset. Bank- based systems appear to have an advantage in terms of providing a long-term stable financial framework for companies. Market-based systems, in contrast, tend to be more volatile but are better able quickly to channel funds to new companies in growth industries (Vitols et al. 1997). A second key distinction between financial systems is the degree to which the state is involved in the allocation of credit. State involvement in credit allocation can turn the financial system into a powerful national resource for overcoming market failure problems and achieving collective economic and social goals. However, financial targeting also runs the danger of resource misallocation due to inadequate reading of market trends or ìclientelismî (Calder 1993).

While every country has a different mix of institutional arrangements, these two dimensions are useful for identifying broad distinctions between countries in capital- market dynamics. For example, a quantitative comparison of Japan, Germany, and the United States in the mid-1990s along the first banks versus markets dimension indicates a major distinction between the first two countries on the one hand and the United States on the other. The banking systems in Japan and Germany account for the majority of financial-system assets (64 and 74 percent, respectively), whereas banks in the United States (with about one-quarter of total financial-system assets) are only one of a plurality of financial institutions. Altogether over half of the combined assets of the nonfinancial sector (assets of the financial, household, company, government, and foreign sectors combined) in the United States are securitized versus only 23 percent in Japan and 32 percent in Germany. Particularly striking is the relatively small proportion of securitized company liabilities in Japan and Germany in comparison with the United States (15.4 percent and 21.1 percent versus 61.0 percent).

The relative advantages and disadvantages of different structures of the financial system for economic growth have been a long-debated issue in economics. On the one hand, Hamilton (1781) argued that “banks are the happiest engines that ever were invented” for spurring economic growth. Gerschenkron (1962) underlined the crucial role of universal banks in German industrialization between the middle and end of the nineteenth century. Similarly, Calomiris (1995) compared the American and German systems of investment between 1870 and 1914 and argued that the German system was Superior. Moreover, Kennedy (1987) claimed that the failure of British financial intermediaries to behave as German universal banks did hamper British economic performance in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. On the other hand, Bagehot (1873) and Hicks (1969) claimed that financial markets played an important role in the UK’s Industrial Revolution.

Our starting point is the observation that different financial systems have evolved in different places through time. As a result, there are differences across countries in the level of financial system development and its structure. The basic functions of the financial system, however, have remained constant through time and across countries. What differs across countries is the quality of the functions provided by the financial system to the economy, which indicates its level of development. In the following section, we will discuss the main functions of the financial system and emphasize the differences in the quality of services provided by banks and markets to the economy. The importance of banks and markets in fulfilling their functions indicates their structures, which are defined as the mix of financial markets, institutions, instruments, and contracts that prescribe how financial activities are organized at a particular date (Levine 1997, 2005). To evaluate whether one system has performed better than another over time, it is important to understand how the financial systems are structured, and the determinants as well.

In the literature, the classification of the financial system typically follows a binary approach (Fohlin, 2012). It often focuses on the dependence of savers and firms on banks or capital markets and draws a distinction between countries with market- and bank-oriented systems. Bank-oriented systems are those displaying high levels of bank finance, equity holding by banks, long-term relationships, close monitoring and active corporate governance by banks. Typically, bank-based financial systems correspond to countries in which commercial banks are mainly universal. In contrast, market-oriented financial systems support large, active securities markets, and firms use market-based financing. In market-based financial systems, banks are very often specialized with an important group being investment banks. This oversimplified characterization provides only a partial picture of the financial system, so some authors classify the financial system as relationship-based or arms-length systems, which captures the degree of separation between investor and firm (Rajan and Zingales, 2002).

In theory, every country has one type of financial system, which falls into one of the distinct categories. In practice, however, the distinction between bank- and market- oriented systems or arms-length and relationship-based financial systems is difficult. The rapid changes in the financial industry in recent decades have further complicated the distinction. In reality, there is no clear-cut distinction between financial systems, and the classifications fit only in a rough manner empirically. Why the differences in the structure of the financial system have prevailed across countries is not well understood. A substantial body of literature tries to explain the differences across countries from different perspectives, including law, politics, and culture. In addition, a number of papers have argued there is a positive nexus between financial system development and economic growth. In recent decades, there has been a rapid growth in financial innovations, such as securitization, which increases the reliance of banks on capital markets as a source of finance. This trend not only leads to the growth of financial intermediation outside the banking system but also has important implications for the role of banks in financial markets. Consequently, the structure of the financial system is now more complex than it used to be. These changes may benefit the general economy by increasing credit availability and reducing the cost of capital, while at the same time, they may make the financial system more fragile and further amplify economic volatility, as mentioned in the financial crisis of 2007.

Financial Architecture and Performance

Markets as well as banks perform vital functions in an economy, which include capital formation, facilitation of risk sharing, information production and monitoring. The case for bank-based or market-oriented systems could be made based on the relative effectiveness with which banks or markets execute these common functions. At the extreme, some argue that market-based systems are inherently superior (see Macey (1998) and the recent literature on global convergence of corporate governance (e.g. Coffee (1999)) while others underscore the intrinsic value of banks (e.g. Gilson and Roe (1993)). By implication, adopting the superior financial architecture would enhance economic performance. There are also middle-ground positions on the role of financial architecture. Some argue that financial architecture is inconsequential to the real sector with the belief that banks and markets are complementary in providing financial services, and that neither has a natural advantage in the provision of all services. Others argue that financial system architecture matters in that markets or banks may have a comparative advantage in delivering particular services depending on the economic and contractual environments of the country.

Financial Architecture As A Matter of Indifference

The indifference view which is partly based on the functional perspective to financial systems, stresses that a financial system provides bundles of services such as project evaluation, risk sharing, information production and monitoring. It is the quantity and quality of these services in an economy that matters, and not the venue by which they are provided (see Levine (2000) for an extensive review of this perspective). Hence, the market orientation of the financial system is of secondary importance, since both banks and markets provide both common and complementary services. This view has recently received more strength from the law and finance literature which stresses the importance of investor-protecting legal codes and their enforcement in enhancing financial services that promote economic performance (Laporta et al (1997, 1998, 1999), see also Levine (2000)). La porta et al (1999) suggests that differences in depth and quality of financial systems as predicted by the quality of the supporting legal system is more important than distinctions in terms of bank or market orientation.

Financial Architecture Relevance

The perspective that holds that financial architecture matters rely on distinct differences in the types of services provided by markets and banks. A key attribute of financial markets – a feature that distinguishes them from banks – is that equilibrium prices formed in markets provide valuable information (about the prospect of investment opportunities) to real decisions of firms which, in turn, affect market prices. This is what is called the ‘information feedback’ function of markets. Tadesse (2000) provides empirical evidence that this market-based governance has a positive impact on economic performance. In particular, it has an effect of enhancing economic efficiency. The relative importance of a given financial architecture (market vs banks) depends on the value of this market information (demand side argument) and how effectively markets perform this information aggregation function (supply side argument).

On the supply side, the relative merits of markets versus banks depend on the effectiveness with which markets can perform their information feedback function. Well functioning markets rely on contracts and their legal enforceability. Impediments to markets such as weak contractability reduce the supply of information aggregation as a market function. In this situation, a bank-based architecture, which survives in weak contractual environments, could be of superior value. Rajan and Zingales (1998b) postulates that the relative merits of the financial architectures are a function of the contractability of the environment and the relative value of price signals. Bank based systems naturally fits in situations with low contractability combined with high capital scarcity relative to investment opportunity. Market –based systems work better in situations of high contractability and high capital availability relative to investment opportunities (implying high value of price signals).

On the demand side, one would expect a revival of market-based systems in situations where information aggregation is especially valued. However, market generated information is not always considered useful for various reasons. First, not all decision environments benefit from price signaling. Allen (1993) and Allen and Gale (1999b) argue that the information feedback from markets would be most valuable in decision environments, such as new industries, in which consensus are hard to achieve about the optimal managerial rule due to rapid technological change, and constantly changing market conditions. Conversely, the value of information aggregation is lower in economies that are dominated by firms with less complex decision environments.

Second, the prevalence and severity of moral hazard attenuates the value of information feedback by financial markets. Boot and Thakor (1997) argue that banks provide a superior resolution of post-lending moral hazard resulting from potential distortions in firms’ investment choices while markets provide improvements in real decisions through the information aggregation. However, the greater the moral hazard problem, the lower is information acquisition in the financial markets, and the smaller the value of market information in affecting real decisions. The value of market information is, therefore, lower in economies dominated by firms that are prone to moral hazard problems (e.g. poor credit reputations). This implies that, other things constant, a bank- based system might fit better to economies dominated by firms prone to more agency problems.

Third, the value of price signals also depends on the ease with which project selection could be accomplished in its absence. The value of price discovery is higher in situations where real decisions could be least likely distorted if not based on external information. Rajan and Zingles (1998b) points that in situations of extreme capital scarcity relative to available investment opportunities, real decisions, even in the absence of market information, are less likely to go wrong because, in this case, it would be relatively clear as to which investment would be profitable. Hence, all other things constant, the more capital abundance relative to investment opportunities in an economy, the higher is the value of information aggregation, and the more desirable a market-based architecture; and vice versa.

The foregoing implies that the real consequences of financial architecture (market-based vs bank-based) should depend on a host of country specific factors including the contractual environment of the economy, the associated severity of agency problems, and the degree of complexity of the decision environment in the economy. In the sections that follow, we examine empirically the real consequences of financial architecture across economies of differing contractual environments and differing prevalence of agency problems. We expect market-based architectures to perform better in countries with stronger contractual environment, and bank-based systems to fare well in contractually weak economies. This is what we call the contractual view to financial architecture. We expect bank-based systems to perform better in economies with firms t fare better in countries with firms that are less susceptible to these problems. This is the agency view to financial architecture.

What Are Components of Financial System in General

Generally, the financial system in a country is considered designing the sourcing of private sector state financing for the economic development of a country. The most widely accepted theory, the timing of industrialization (TOI) thesis, argues that key differences in national financial systems can be traced back to their respective industrialization phases (Gerschenkron 1962; Lazonick and OíSullivan 1997). In countries where this process started earlyóthe United Kingdom is the key example firms were able to finance new investment gradually from internally generated funds or from securities issues in relatively developed financial markets. Firms in countries in which industrialization started later, however, faced a double disadvantage relative to their advanced competitors in early industrializing countries. First, internally generated finance was inadequate (or, in the case of newly founded firms, nonexistent) relative to the large sums needed for investments in ìcatch-upî technologies and infrastructure. Second, market finance was difficult to raise because securities markets were underdeveloped and investors were more inclined to invest in safer assets such as government bonds. Thus only banks could gather the large sums of capital required, take the risks involved in such pioneering ventures, and adequately monitor their investments. Once established, bank-based systems have a strong survival capacity. This interpretation of history provides support for the recommendation that developing countries follow the model of bank- based development (Aoki and Patrick 1994).

TOI draws on both the German and Japanese cases to back up its claim that bank-based systems were necessary for late industrializers to catch up with more developed countries. For TOI, Germany is the premier example of a developmental bank-based system. In the second half of the nineteenth century, particularly after 1870, joint-stock banks active in both lending and underwriting activities were established. These ìmixedî banks enjoyed a close (Hausbank) relationship with many of their industrial customers. In addition to getting the lionís share of financial services business, these banks often held substantial stock in and appointed directors to the supervisory boards (Aufsichtsr‰te) of these companies. TOI claims that these mixed banks played an essential role in the rapid industrialization of Germany after 1870, not only through organizing large sums of capital unobtainable in nascent capital markets but also through providing entrepreneurial guidance (Gerschenkron 1962). The capacity of these banks for strategic planning was further demonstrated through the organization of rationalization cartels to deal with the overproduction crises in basic industry in the early twentieth century (Hilferding 1968). Finally, it is claimed that the three largest joint-stock banks (Deutsche Bank, Dresdner Bank, and Commerzbank) continued to use their close links with large industrial companies to act as the locus of private industrial policy in the postwar period (Deeg 1992; Shonfield 1965; Zysman 1983). The role of German banks is most frequently contrasted with the U.K. clearing banks, which allegedly have beenmore interested in short-term commercial finance than long-term industrial finance (Ingham 1984). At the end a financial system evolved for the private sector sourcing of finance called Bank Based and Market Based. Meaning the private sector lead industrialization financing source would be from the banking system or from the capital market-by issuing shares, debentures, and bonds listed in stock market, through private equity and alternative financial instruments. In case of State, the governments also finance the infrastructure from issuing bonds and approved financial instruments, revenue collections, borrowing from local and foreign market.

Bank Based And Market Based Financial System

As in the corporate finance literature, we distinguish between bank-finance and market-finance based upon their involvement with investment projects. Banks are typically more engaged in project selection, monitoring firms and identifying promising entrepreneurs, while market-finance (corporate bonds and equities) is an arm’s length transaction, with little involvement in a firm’s investment decisions. Specifically, we adapt Holmstrom and Tirole’s (1997) agency problem: borrowers may deliberately reduce the success probability of investment in order to enjoy private benefits. Outside investors (the mar- ket) are too disparate to effectively control a borrower’s activities. Financial intermediaries, on the other hand, monitor entrepreneurs and (partially) re- solve the agency problem. But since monitoring is costly, bank finance is more expensive than market finance. A key determinant of financing choices is an entrepreneur’s initial wealth. Entrepreneurs with lower wealth have more incentive to be self-serving than wealthier ones. One way to mitigate this incentive gap is to borrow, at a higher rate, from a bank and agree to being monitored. In contrast, wealthier entre- preneurs rely more on market finance as they face less of an information gap.

In certain cases, for instance when the fixed cost of modern sector activities are large, even bank monitoring is not a sufficient substitute for entrepreneurial wealth – the poorest entrepreneurs are unable to get any type of external ((Mayer, 1988). See Allen and Gale (2001) for more recent evidence. A bank-based system, where intermediation plays a key role, or a market- based system, where all lending is unintermediated, evolve endogenously in our model. A bank-based system emerges when monitoring costs are modest and when agency problems are significantly extenuated through monitoring. When agency problems are not particularly severe, or when monitoring is expensive, a market-based system emerges. The growth rate under either regime is a function of the efficiency of the system – better-functioning legal systems make contracts easier to enforce and reduce monitoring costs as also the cost of direct lending. Investment is higher, as is the growth rate of per capita income. In this, our results square well with the ‘legal-based’ view espoused more recently by LaPorta et al. (1997, 1998) and for which Levine (2002) finds strong cross-country evidence.

Although neither a bank-based nor a market-based system is specifically better for growth, our model suggests some advantages to having a bank-based system. In particular, since bank monitoring substitutes for entrepreneurial wealth, it enables all modern-sector firms to make larger investments than is possible under purely unintermediated finance. It also lowers the minimum en- trepreneurial wealth required to obtain external finance so that the traditional sector is smaller under a bank-based system. Hence, even when a bank-based and a market-based economy grow at similar rates and have similar wealth distributions, per capita GDP in the former is permanently higher. Financial and legal reforms which reduce agency problems make it easier for modern-sector entrepreneurs to borrow. This raises the investment rate, and hence GDP growth, under both types of financial system. However, in a bank- based system, these reforms also have a level effect on per capita income. By lowering the minimum wealth needed to raise external finance, they assist traditional sector entrepreneurs to enter the modern sector faster. This speeds up structural transformation – the traditional sector declines in size and the modern sector expands faster. In contrast, reforms in a market-based system may leave the traditional sector relatively worse-off unless they specifically reduce the costs of bank intermediation.

Financial Structure And Economic Growth

Answer: In the literature, three main bodies can be distinguished that investigate the relationship between financial structure and economic growth. The first one directly examines the impact of the structure of the financial system on economic growth. Initially, studies comparing financial systems focussed on one country or only a small set of developed countries. Goldsmith (1969) pioneered this line of research as he tried to evaluate whether the financial structure influences the pace of economic growth. In this study, Goldsmith relied on a careful comparison of the financial systems in Germany and the United Kingdom, but his results on its impact on economic growth were ambiguous. Allen and Gale (2000) discuss financial systems in five industrial economies. Based on the relative importance of banks to capital markets in allocating resources to firms, they argue Germany, Japan and France have bank-based financial systems, while the United States and the United Kingdom have market-based financial systems. They note that all these countries have similar long-run growth rates. Hence, the marginal contribution for having different types of systems on real economic growth is not significant within this small group of developed countries in the long run. In contrast, Arestis, Demetriades, and Luintel (2001), using the five developed countries and time-series methods, argue that while equity markets in the developed countries may be able to contribute to long-run output growth, the influence of the stock market is much smaller than that of banks. Based on this, they argue that bank-based financial systems may be more growth-promoting than market-based financial systems.

Nevertheless, it is not clear from these studies whether their findings can extend to different countries across the world. Indeed, early on, Goldsmith (1969) already expressed the need to further investigate the relationship between the financial structure and economic growth using a larger set of cross-country data. Demirgüç-Kunt and Levine (2001) and Levine (2002) have examined the relationship by employing a broad data set covering 48 countries from 1980 to 1993. They find that neither bank-based nor market-based financial systems are particularly effective in promoting economic growth. Their results were robust to an extensive array of sensitivity tests that included different measures of financial structure, alternative econometric methods, different data sets and more control variables such as legal factors. Moreover, the results changed only slightly when they were looking at different extremes, which are countries with very well-developed banks but poorly developed capital markets and countries with poorly developed banks but very well developed capital markets. However, Demirgüç-Kunt and Levine (1996) find that countries with a well-developed stock market also have well-developed banks and non-bank financial intermediaries. This suggests that intermediaries and markets are complements in providing growth-promoting financial services.

This conclusion has been supported by Beck et al. (2001), who document that countries do not grow faster with either type of financial system. Furthermore, they emphasize that what matters more for the finance-growth nexus is the efficiency of the legal system in protecting outside investors’ rights. Rioja and Valev (2006) find that bank-based financial systems are associated with stronger capital accumulation. Neither of these studies finds empirical support that bank-based or market-based financial systems foster long-run economic growth.

In contrast, Tadesse (2001) finds that the difference between bank-based and market-based financial systems is important in explaining economic growth. Using a sample of 36 countries from 1980 to 1995, he shows that in countries with an underdeveloped financial system, bank-based systems outperform market-based systems. However, in countries with developed financial systems, market-based systems outperform bank-based systems. He documents that a lack of fit between the country’s financial system architecture and its legal institutions can restrain economic performance. Similarly, Luintel et al. (2008) find that the financial structure significantly explains output levels in most countries. They argue that the complete absence of cross-country support for a financial structure reported by certain panel or cross-section studies may be a result of inadequate accounting for cross-country heterogeneity. Taking into account the problems of existing studies and the use of time series and a dynamic heterogeneous panel method, they document that the financial structure and financial development affect output levels and economic growth. In a recent study, Demirgüç-Kunt et al. (2013) find consistent evidence that with the growth of economic activities, the association between an increase in real output and that in bank development decreases, while the association between an increase in real output and that in securities market development becomes larger, suggesting the changing importance of banks and equity markets with the development of the real economy.

The existing empirical evidence suggests that both bank- and market-based financial systems are important for economic growth. Huybens and Smith (1999) argued that it is possible that markets and banks are complements rather than substitutes and it is the efficiency of the financial sector as a whole that is of importance. Levine and Zervos (1998) confirms that higher stock market liquidity or greater bank development is positively associated with contemporaneous and future rates of economic growth, capital accumulation, and productivity growth, irrespective of the development of the other. Thus, a view emerged in the literature that both financial structures might be substitutes in fostering long-run economic growth (Levine, 2002; Beck and Levine, 2004), which supports the recent research on financial crises that we will discuss in the next section of the chapter.

In the past decade, a new perspective emerged on the relationship between financial system development and economic stability. The ‘too much finance’ view indicates that having a too large financial system may have a negative impact on economic stability and growth. This theory is strongly supported by the global financial crisis of 2007-2009, where Rajan (2005) warned prior to it that the on-going evolution of the financial system may lead to a large and complicated system and to an accumulation of vulnerabilities that may then result in a financial disaster. Consequently, currently the question is whether there is a threshold when a financial system supports economic growth and whether one structure of the system is better than the other for economic stability.

Cecchetti and Kharroubi (2012) show the relationship between financial development and economic growth is non-linear. It means that the level of financial development supports economic growth only to a point, after which it becomes a drag on growth. They estimate that the turning point is approximately 100 per cent of GDP for private credit and 90 per cent for bank credit. Similarly, Arcand, Berkes, and Panizza (2015) find that the relationship between financial development and economic growth has an inverted U-shape, where they estimate the turning point to be when credit to the private sector reaches 100 per cent of GDP. Law and Singh (2014) using a different methodology estimate the threshold at approximately 88 per cent of private credit to GDP and report an inverted V relationship.

Sahay et al. (2015) expanded the work and created a financial development index comprising both financial institutions and markets and three dimensions of financial development: depth, access, and efficiency. Using the index, they confirm the non-linear relationship between financial system development and economic growth. According to them, the weakening effect of the financial system on the economy is mainly due to financial deepening, rather than from greater access or higher efficiency. Seven and Yetkiner (2016) extended the research by analysing the impact of the structure of the financial system on economic growth in countries grouped based on the income level. They report that banking development is beneficial to growth in low- and middle-income countries, yet harmful in high-income ones. In contrast, they show that the development of stock markets favour growth in middle- and high-income countries.

Sahay et al. (2015) show that the pace of financial development also matters. They document that when the development proceeds too fast, deepening financial institutions can lead to economic and financial instability. Silvia et al. (2017) confirm the non-linear relationship between financial development and economic growth. They also find that financial development simultaneously and more than proportionally raises growth volatility. A more detailed description on financial development and volatility is presented in the chapter by Loayza, Ouazad and Ranciere.

Gambacorta et al. (2014) report that banks and markets differ considerably in their moderating effects on business cycle fluctuations. On the one hand, they suggest that banks smooth the impact of the economic recession, as they are more likely to supply loans during a normal downturn. On the other hand, they find that their shock- absorbing capacity is impaired when the downturn is associated with a financial crisis. In those situations, they find that in countries with bank-oriented financial systems, the recessions are three times more severe than in countries with a market-oriented financial structure.

Langfield and Pagano (2015) attribute the rise in economic volatility to the increasing role of the banks in the European financial system. They document that the bank-based financial structures are associated with more systemic risk-taking by banks. In addition, the results indicate that the economic growth tends to be lower in bank- based financial structures, particularly during times of large drops in asset prices. Hence, they recommend that reducing the bank bias should therefore be an important intermediate objective of financial policy. The switching of the structure of the financial system seems to be quite difficult, as we discuss in the next section. Moreover, Deidda and Fattouh (2008), using a theoretical model, show that a change from a bank- dominated financial system to a system with both banks and markets can have a negative effect on economic growth.

Consequently, the current research shows that the relationship among financial system development, structure and economic growth is quite complex, but there is currently a growing consensus that ‘too much finance’ can be harmful for economic growth. However, most of the empirical studies utilized only private credit as financial system development indicators. Given that equity and bond markets are also principal sources of finance, it is important to understand better their role and its relationship to economic growth. Consequently, more research is needed on the structure of financial systems and economic growth, which will take into account the recent findings on the impact of financial development on economic growth and stability.

Financial Structure And Political Influence

Another explanation for the design of the financial system is based on political factors. Given the importance of financial systems for economic growth, it is not surprising that the policies for the financial sector are often on the top of policy makers’ agendas, particularly during crises. A large number of papers discuss the impact of politics on the finance-growth nexus, which can be roughly divided into two different views. We will go through both of them in turn.

The first view basically argues that policy makers act in the best interest of society, ultimately maximizing the growth benefits for the entire economy. Therefore, the market failures inherent in financial systems require government interventions beyond regulation and supervision. For example, Song and Thakor (2012) develop a theory of how a financial system is influenced by political intervention that is designed to expand credit availability. They show that the relationship between political intervention and financial system development is non-monotonic. In the early stage of financial development, the size of the market is relatively small, and politicians intervene by controlling some banks and providing capital subsidies. In the intermediate stage when the sizes of both the banking sector and market are larger, there is no political intervention. However, in the advanced stage when the financial sector is most developed, political intervention returns in the form of direct-lending regulations. The second view argues that policy makers act in their own interest, maximizing private rather than public welfare. Therefore, interventions by politicians in the event of a crisis involve diverting the flow of credit to politically connected agents instead of improving social welfare. Rajan and Zingales (2003, 2004) are good examples of this view. They argue that the structure of the financial system may experience substantial reversals when a political majority decides to alter the legal framework. A financial system will develop towards the optimal structure but will be hindered by politics, which are often influenced by powerful incumbent groups. Thus, financial development and changes in structure can occur only when the country’s political structure changes or when incumbents want the development to occur. Similarly, Cull and Xu (2013) document that financial development is driven by the political economy, and furthermore, financial development may reflect the interests of the elite, rather than providing broad-based access to financial services, by modelling the choice of investor protection as a legislative or enforcement choice taken by politicians. Feijen and Perotti (2005) also show that access to external financing can be used by incumbent political and economic elites to protect rents and entrench their dominant position (see also Perotti and von Thadden, 2006)

U.S. financial history provides numerous examples of political influence affecting the development of the banking system. The same is true for emerging economies such as China. By studying the political economy of regulation in the U.S. during the 18th and 19th centuries, Benmelech and Moskowitz (2010) argue that financial regulation is the outcome of private interests using the coercive power of the state to extract rents from other groups, which is further associated with lower future economic growth. They document that the tension between private and public interests provides an explanation for the variation in usury laws observed across states and time. States adopted laws to hamper competition from neighbouring states and lower their own cost of capital. The link between private interests and financial regulation also suggests the endogenous relationships between financial development and growth. Kroszner and Strahan (1999) find that the private interest theory of regulatory changes can account for the pattern of bank branch deregulations in the 1970s and 1980s in the U.S. They argue that innovations that began in the 1970s altered the value of restrictions to the affected parties and the subsequent competition among interest groups can explain deregulation. However, some of their results also show that deregulation occurs earlier when small banks are in a weak financial position, which is still consistent with the public interest theory. Studies on China’s financial sector also suggest that political factors are strongly associated with the bank loan granting and equity financing (see, e.g., Ayyagari, Demirgüç-Kunt and Maksimovic, 2010; Fan, Wong and Zhang, 2007).

Some other studies have tried to use the political structure as a basic factor to explain financial development and economic growth. Both theoretical and empirical studies show that political and economic elites can manipulate institutions (Glaeser et al., 2003). Powerful political interest lobbies influence the type of property rights protection and the degree of investor protections that suit their interests best. Pagano and Volpin (2005) show that proportional electoral systems are conductive to weaker shareholder protection and stronger employment protection, which benefits entrepreneurs and workers while damaging outside shareholders. Other political variables, such as ideological factors, voting thresholds and the tenure of the democratic system, appear to affect regulatory outcomes.

Therefore, political institutions seem to have a first order effect on economic and financial stability in the literature. Poor transparency and corruption or weak regulatory institutions increase the probability of a banking crisis after financial liberalization (Acemoglu et al., 2003). The issue is, even when liberalization leads to a higher level of GDP growth, the distribution of gains remains a relevant question to ensure its sustainability. For example, in Latin America, financial transfers following banking crises have targeted privileged income classes. In the meanwhile, default costs are usually socialized through regressive policies, such as inflationary bailouts or fiscal cuts, that disproportionately hurt weaker social groups and median income households (Das and Mohapatra, 2003). Bekaert, Harvey and Lundblad (2006) show that the volatility of the economy in terms of consumption growth following equity market liberalization depends on the economic, financial, social and political conditions within a country. If a country has a relatively well developed banking sector, less external and internal conflicts, a large government sector and a relatively brighter economic outlook, then consumption growth tends to be less volatile after the liberalization. In this sense, political factors are more important than legal factors in driving economic volatility.

History, Culture And Important Factors Influence Financial Structure

In recent years, a number of studies have pointed to other theories that try to explain the development and structure of the financial system. One of these theories advocates that financial systems have a path-dependent nature. It means that financial system development and its structure is shaped by the initial conditions and historical evolution of the country. Ang (2013) shows that the existing differences in financial development between countries can be explained by the variations in their levels of state experience over the last two millennia. His results suggest, however, that state history has stronger explanatory power for current financial development than financial development over the last half century. Moreover, his results indicate that state history positively affects both bank-based and market-based financial systems and there is no systematic difference between them. Monnet and Quintin (2005), furthermore, argue that history matters not only for the development of the financial system, but may also explain its current structure. On the one hand, Monnet and Quintin (2005) argue that the legal differences in countries with bank-based and market-based financial systems are fading as a result of government efforts to deregulate and liberalize financial systems around the world. On the other hand, institutional convergence has not implied financial convergence across countries. Monnet and Quintin (2005) suggest that financial systems will continue to differ for a substantial period even if their basic characteristics become identical. The argument is based on the assumption that the historical fundamentals of financial systems are relevant and any change in structure is costly. Thus, they claim that the previous structure of a financial system explains and determines the existing structure. The work of Monnet and Quintin (2005) provides some explanation as to why financial structures persist in countries following changes in the institutional framework. However, their work does not provide a clear explanation of why determinants change over time.

Another perspective presents the endowment theory that ties the development and structure of the financial system to the colonial conditions such as geographic factors and the disease environment in shaping subsequent institutional and financial development. Acemoglu et al. (2001) argue that European colonizers pursued different types of colonization strategies with different associated institutions. In some countries, the Europeans installed property rights institutions that protected private property contracts, which subsequently promoted financial development. Acemoglu et al. (2001) underlined, however, that colonial experience is only one of the many factors affecting institutions and henceforth also financial development.

A related theory has been proposed by Stulz and Williamson (2003), who argue that culture matters for financial development since it affects values, beliefs, institutions and how resources are allocated in an economy. Stulz and Williamson (2003) indicate that a country’s principal religion predicts the cross-sectional variation in creditor rights better than the origin of its legal system. They report also that religion and language are important predictors of how countries enforce rights. Based on their findings, they argue that Catholic countries protect the rights of creditors less than do Protestant countries, which may explain why Catholic countries have less developed financial systems. A similar perspective is presented by Kwok and Tadesse (2006), who argue that national culture may be an important determinant of a country’s financial structure and presented evidence that countries characterized by higher uncertainty avoidance (risk aversion) are more likely to have a bank-based system.

Finally, Allen et al. (2016) suggest that a country’s financial system adapts to the needs of the real economy. They show that in countries with a well-developed service sector in the economy, a market-based system is more likely to emerge. In contrast, countries with large industrial sector (fixed assets) are more likely to have a bank-based system. Consequently, their research suggests that specialization patterns in a financial system are influenced by the composition of the economy, which in turn is determined by a country’s endowments. This variety of approaches suggests that there is no consensus with respect to the determinants of financial structure. Moreover, economic and legal factors show strong relationships to financial system design and development, but causality is difficult to establish. Hence, although social and political context play important roles in shaping institutions, it is difficult to pinpoint reliable and consistent relationships among economic, political, legal and financial variables. Moreover, the recent results show that even political and regulatory intervention influences system design and the political system type does not have any systematic or predictable effect.

Financial System Structure For Bangladesh

The IMF (2011) study on Private Sector Financing for the period 2002-2007 was conducted by Julion Allard and Rodolph Blavy on 17 developed countries with regards to their dependency on Market-Based and Bank-Based as the source of Private sector financing. The study ranked the countries with their sourcing dependence greater or equal to 50% from Market have been categorized as Market-Based economy. The other countries those sourcing of private sector greater or equal to 50% financing come from the bank are grouped as Bank-Based economy. Thus the study reveal that Seven countries are market-based and ten countries are bank-based. Australia, Canada, Denmark, Finland, France, the United Kingdom, and the United States are classified as market- based. Austria, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Japan, Netherlands, Norway, Portugal, Spain and Sweden are bank-based. Given the sensitivity of the classification to data sources, in particular for countries in the middle of our sample, we identify two groups that maximize within-group homogeneity: “strongly market-based” economies and “strongly bank-based” economies. Four countries are strongly market-based—the United States, Australia, Canada, and the United Kingdom— and four are strongly bank-based— Belgium, Portugal, Spain, and Austria. (Sources: National Financial Account, OECD.)

Carlin/Mayer (1999b) analysed the relation between the growth rates of 27 industries in 14 OECD countries and the interaction of industry-specific characteristics with financial variables. They found that in particular the growth of industries relying on R&D is strongly affected by financial variables. The estimates are less robust as regards fixed capital formation. Thus, finance mainly stimulates economic growth by affecting investment in R&D whereas the financing of physical capital accumulation is only of minor importance. They regard their results as providing evidence that the superiority of a particular form of corporate control and financing does not depend on general considerations. Instead, the optimal financial relations for an enterprise depend on the type of economic activity the corporate is involved in. Financing via stock markets may be better suited to high-risk and innovative activity. Bank finance may be more appropriate for more traditional investments that rely on the provision of long-term finance. Also the analyses of Beck/Levine (2000) and Demirgüc-Kunt/Maksimovic (2000) on the firm level demonstrate that the financial structure does not affect the quantity of external financing available to firms.39 New firms and expanding firms do not grow significantly different in a market-based or a bank-based financial system. Instead, the overall level of financial development matters for the growth prospects of new firms. A structural difference that Demirgüc-Kunt/Maksimovic (2000) observe is that security markets facilitate long-term financing and banking systems facilitate shortterm financing. This insight contrasts with the result by Carlin/Mayer above, who see the main merit of banks in providing long-term finance.

Completeness And Adaptability of Financial Structure

Recently, the debate about the optimal financial structure has been put into a new light. It is in particular the importance of legal issues that has raised doubts about the policy relevance of the “bank versus market” approach, given that policy makers are unable to affect the legal origin of the economy.40 Both, financial markets and financial intermediaries, provide capital services, which are important to spur economic growth. Whether a bank-based or a market-based system provides financial services appears to be of secondary importance, which is in line with the empirical evidence presented above. Overall, it turns out that existing financial structures are rather complex with the above mentioned distinction between a bank- and a market-based financial structure falling short of providing a reasonable approximation of reality. Financial structures in developed countries display both categories and differ mainly in the extent, to which markets or banks deliver financial services. For instance, bank lending has an important market share even in the USA, with the country’s financial system being widely perceived as the prototype of a market-based system. In addition, banks are not the only financial intermediaries. Insurance companies and investment funds often also play prominent roles in the allocation of savings. Furthermore, theoretical reasoning permits plausible arguments in favour of both financial markets and banks as providers of capital while empirical research has so far not been able to establish a clear case for one or other of the mentioned prototypes. Instead of focusing on the difference between banks and markets, attention has shifted towards the completeness and adaptability of the financial structure. These issues will be considered in the subsequent chapter. Stulz (2000) regards it as essential that a bank-dominated system be accompanied by active financial markets, which serve as an alternative for enterprises in getting funds thereby reducing the market power of banks. For banks or other financial intermediaries, it is furthermore useful if an active financial market exists because it allows banks to limit their lending to large customers. This seems to be of importance if enterprises are large in comparison to the bank or if they are growing rapidly. Financial markets provide an exit clause for banks through offering enterprises their assistance in going public, which implies the issuance of equity or corporate bonds. Over the life-cycle of firms, their financial needs are likely to change. Small and young enterprises are likely to benefit from the service of banks to provide financing in stages while the bank learns how the enterprises evolve. Small firms may also value that banks provide their services at low transaction costs compared to financial markets. More mature and larger firms rely more on financial markets finding it favourable to lend large sums by issuing bonds or equity. Overall, it is important that the financial structure is complete offering financing through banks and financial markets and being sufficiently adaptive to allow the evolution of financial intermediaries that specialise in financing the needs of small enterprises. In this context, venture capitalists are regarded as hybrids that fill the gap.41 The same principles might hold for countries. As the economies become more mature and the recent technological advances require investment into immaterial capital to a larger extent than in the past, a financial structure with the ability to adjust should develop a bias towards market elements. In Germany and Japan, who have for long been regarded as bank-oriented systems, recent developments suggest that financial markets have become more important. For instance, a rising importance of securitisation, the increasing issuance of equity by large corporations and the formation of risk capital markets have increased the importance of funding via the market in Germany. In Japan, the banking crises of the 1990s have diminished the role of banks in the economy.

How Are Financial Structures Related to Structural Change And Technical Progress?

The discussion on the determinants of economic growth has shifted in recent years from the analysis of factor accumulation towards the analysis of technical progress and its determinants. Endogenous growth approaches stress the importance of R&D in generating knowledge and of innovative entrepreneurs using this knowledge to introduce new products and processes in business. Empirical research attaches crucial importance to R&D activity, human capital formation and the incentives of entrepreneurs.42 Financial patterns are likely to influence innovative entrepreneurs along the lines analysed in section 4.2. In addition to determining the costs of capital, financial structures influence incentives through the evaluation of projects and the way corporate control is exerted. In this connection, financial structures can be either preservative or supportive of structural change. This section attempts to derive evidence of this feature from two sources. The first is the extent of structural change in the financial system itself, showing its ability to adapt and to exploit technical advances. The second source is the completeness of the financial structure, which is the extent of coverage of the innovative enterprises’ financial demands.

Impact of Technological Progress on The Production Process of The Financial Sector

Information and communication technologies are widespread in the “production process” of the financial sector. Thus, technological progress can be expected to change the organisation of financial activity. The availability of automatic machineryand large processing power has already enabled financial intermediaries to streamline activity. The spread of ATM and the reduced density of the branch network are visible signs of this development as regards the retail market. Concerning the wholesale market, the development of financial innovations as well as the remote access to financial markets at different locations, for instance, would not have been possible without the emergence of information technologies. The management of information has become less costly by the use of mainframe computers in the last decade. The recent technical advances relevant for the financial sector are more communication related than related to processing power. New communication technologies facilitate different means of access for customers to their financial intermediaries. The replacement of personal services by remote banking is estimated to yield considerable cost reductions. Transactions via telephone are estimated to cost 40 to 70 % less and those via the internet are estimated to reduce costs to 1 – 25 % in comparison to manually handled transactions.50 Productivity growth in the financial sector is hard to measure owing to difficulties in pinpointing the sector’s output. For the US financial sector, Bailey and Lawrence (2001) identify an acceleration of labour productivity growth by 3.5 percentage points in the second half of the 1990s to about 6.5 per cent annually. Since the financial sector invested heavily in ICT, the acceleration of productivity is likely to a large extent to be due to the increased usage of new technologies.51 A more indirect effect of the usage of ICT can be derived from the study of Petersen/Rajan (2000). They see the efficiency effect of the increasing use of ICT in financial services in falling transaction costs and present evidence that ICT usage has resulted in a reduced physical distance between banks and small lenders. Thus, access to bank loans has become wider for small business in the USA, which tends to reduce their capital costs and raises their growth potential. According to a review by the European Central Bank (1999b), banks in the EU mainly use new technologies to improve internal information management, but have generally been hesitant to exploit technical advances in their relation to customers. Illustrations of this may be seen in the impact of remote banking on bank’s intangible assets such as customer loyalty as well as in their difficulties in assessing the technological risks of electronic banking. The reluctance of EU banks stands in contrast to observations in the US, where financial institutions have increasingly focused on new technologies. Instead of outsourcing their information technology, they tend to link their core competencies with new technologies in a shift towards information providers.

Composition of Financing of Non-Financial Corporations

Micheal Theil (2001) Director General for Economic Growth in his paper-a review of theory and available evidence in the Economic paper- Finance number 158 July 2001 described the composition of financing of non-financial corporations in the Euro Area in 1999. The paper pointed out that long long-term bank loan represents sourcing of private sector financing 19%, the medium term bank loans 16%, short term bank loans 12%, the estimated loans from other financial institutions 3%, the debt financing securities 10%, The debt securities 10%. IN the equity, the quoted shares represent financing of 24%, unquoted shares 13%, and venture capital represents 3% sourcing of private sector financing in the baskets of European Union countries. However, in Bangladesh, there is no structured study quantifying such sourcing of private sector financing in such structures manner. One can estimate such figures which might not claim through empirical study, can only estimate such figures for comparison purpose. These figures might be estimated as, long term bank loans10%, medium term bank loans 5%, short term bank loans 35-45%, loans from other financial institutions 5%, debt securities 3-5%. The quoted shares 10-12%, unquoted shares and other equities less than 10% and ventures capital financing including private equities less than 1% of whole market requirements. Considering the current state of private sector sourcing of financing, one can conclude that Bangladesh Financial System enjoys ample opportunity to redesign its sourcing of private sector financing for economic growth to compete with other South Asian neighbors, East Asia, Europe, Africa, Latin America and North American Financial System.

Sigurt Vitols [(2001), source-Avery and Ellichausen, 1986)] conducted study on the structure of postwar financial system in the mid 1990s in the paper on the origins Bank-Based and Market-Based financial system in Japan, Germany and the USA. The findings of the paper indicated that proportion of Banking System Assets in total financial system assets (1996) Japan 63.6%, Germany 74.3%, and USA 24.6%, By comparison the Bangladesh can be estimated most likely over 60%. The proportion of securitized assets in total financial assets (1996) accounts for Japan 22.9%, Germany 32..0%, and the USA 54.0%. Compared to those we can estimate for the Bangladesh 25%. The proportion of securitized assets in total household sector assets (1995) accounts for Japan 12.4%, Germany 28.8%, and the USA 5.9%. The comparative figure for Bangladesh can be estimated less than 5%. The proportion securitized liabilities in total financial liabilities of non-financial enterprises (1995) account for Japan 15.4%, Germany 21.1%, and the USA 89.61%. The comparative estimate for Bangladesh may range from 35-50%. The outstanding financial liabilities of public sector accounted for securities (1995) scorded in Japan 71.2%, Germany 56.7%, and the USA 89.6%. The comparative figure for Bangladesh may stand 40%. All the information of this study and comparison of those with Bangladesh shows that well planned Financial System Structure was absent for long to captures the opportunities for economic growth of the country. Time has come to recalibrate and design it properly to pave the path of desired Economic Growth in the most efficient way.

Bangladesh: Effective Financial System For Sourcing of Finance For Economic Growth

Private Sector: Based on discussion this paper, one cannot replace existing financial system overnight rather it takes a long term position. For sourcing of private sector financing for economic growth Bangladesh can move for a model financial system structure. This may be through Banking Cannel 25-45%, This include Commercial banks, Development Financial Institutions for long term financing, Infrastructure Development Bank (converting current IDCOL, IIFC, or any others), HBFC which is a corporation and converting it into Bank and injecting GoB fund at lower interest, Agricultural Development Bank, NBFIs, and Effective Promotion of Investment Banking. Develop Equity Market capable of sourcing Finance 35-50% attracting public and intuitional investors, listed companies, private equity and fund from home and abroad, issuing debentures, and other financial instruments. Creating effective Bond Market in local currency and foreign currency with a share of 20-30% of whole private sector sourcing of fund for long tern finance. Attracting foreign Direct Investment targeting 20-25% of country requirements.

Public Sector: Bangladesh is a country that lost every infrastructure and productive unit in the war of liberation and 23 years of exploitation like Japan in second World War. Soon after II WW Japan started again and created success story by doing economic miracle. Time is for Bangladesh. Government of Bangladesh supplied huge resources to the public sector and developing infrastructure to support enabling better business environment. To implement the vision 21-30 and 41 as developed country public sector financing source would play a vital role. Keeping all these issues in plan Bangladesh needs recasting its financial system structure. These may be from Banks and financial Institutions source 15-25%, Stock Market 10-20%, Bond Market15-25%, and financing from GoB Revenue Department 45-50%. These are the proposals sated here which is estimate. In reality check, the GoB should form a Committee with skilled professional to design a doable Financial System Structure with a specific Terms of Reference defining the timeline for consideration of competent authority.